I have to thank a woman called Rebecca Skloot for giving me an education I won't soon forget.

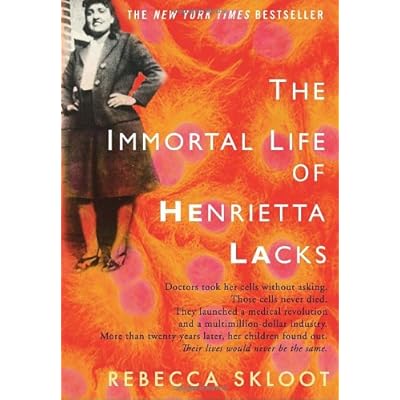

I have to thank a woman called Rebecca Skloot for giving me an education I won't soon forget.I've never met Skloot, and I couldn't pick her out of a photo. But I have read her wonderful book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, and consider it one of the most fascinating books I have stumbled across in years.

In fact, it fractured my mind, sending it along paths and donkey trails I never knew existed.

I started listening to the book cold. I had no idea what I was getting into. It was just sitting in my Audible folder and I needed something to listen to. I loaded it on my phone and hit play.

I don't expect you to do the same. Here is a little teaser.

Lacks was a black woman who was diagnosed with cervical cancer on January 29, 1951.

She was subjected to crude cancer treatment (barbaric to my eyes, though it was cutting edge at the time) in a black-only wing of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

She died horribly nine months later.

And yet she lives on today. Literally.

A doctor took two samples of her cervix without permission, a healthy bit of flesh and a cancerous one. The cells went into a Petri dish and found their way to scientist George Gey.

And in Gey's care something remarkable happened. They survived.

This had never happened before.

Until Lacks' cells were taken, human cells died after a few days outside the body. Lacks' cells did not. Gey could grow them in a lab. He called them HeLa (a nod to Henrietta Lacks) and started shipping them to colleagues around the world - granting this woman a form of immortality.

Since then, Lacks' cells have been used to cure polio, to develop AIDS drugs, used for gene mapping, to test glues and cosmetics and ... well, a mind-numbing variety of other things.

HeLa is really the foundation of much of the medical science of the modern world. There are about 11,000 patents stemming from HeLa cells.

And many members of Lacks' family in Maryland can't afford Medicare.

And so Skloot's amazing story goes, weaving the story of Lacks and her family into medical research and ethics and pure science.

A journalist, Skloot has achieved remarkable balance in the telling. As outrageous as some of the ethical snarls are, they are never clear cut. This is grey matter, baby - history, society, technology, politics and simple ignorance all contribute to the problems that bedevil the HeLa cells and the Lacks family.

Skloot ferreted out the details over nine years, and she was tenacious in the chase. She handles this complex story of the human consequences of scientific discovery with compassion and considerable tact.

At the end, you will probably have shed a tear, unless you are an unnaturally heartless soul.

And, if you are like me, you will marvel at Skloot's accomplishment.

The book lays bare how unbelievably clueless brilliant scientists can be.

It shows how seemingly random events combined with a little luck can alter history for the better.

And, perhaps most important, it demonstrates how even the most overlooked people in society, like a relatively poor black mother in Baltimore, can be extraordinary in ways nobody could imagine.

In this case, a woman on her deathbed provided the means to alter the future of the entire human race, saving untold thousands of lives and helping to build the modern medical economy in the process.

And, until Skloot's book, only a handful of people knew her name.

Remarkable.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot, Crown, published February 2010.